ISEE test preparation, why do it? How much time should be spent on it? THAT MUCH? Is the ISEE different from the SSAT? Those are really good questions.

ISEE test preparation, why do it? How much time should be spent on it? THAT MUCH? Is the ISEE different from the SSAT? Those are really good questions.

The Independent School Entrance Exam (ISEE) and the Secondary School Admission Test (SSAT) are used for private school and boarding school admissions to grades 3-12 and skew way above grade level in what they assess, so just learning test-taking strategies is insufficient. Moreover, earning stanines of 7s, 8s, and 9s requires near perfect section scores. That’s why we recommend a nice long runway to prepare for the ISEE or SSAT. Most of our students are engaged in 1:1 programs meeting twice weekly–once with a literacy specialist and once with a math specialist–for 15-25+ weeks, which translates to 45 to 90 hours of instruction (plus homework). Yes, that much and here’s why.

At My Learning Springboard, we believe that ISEE test preparation, and most other preparation for standardized assessments, should be aligned with and extended from a curriculum framework. What we are doing should tie in closely with what your student is learning or will learn in his or her classroom. All learning is enhanced when it is connected with something that you already know and/or something you want to know. Preparing for an assessment such as the ISEE helps streamline that focus towards a multi-faceted endpoint; not only does your student solidify their foundational skills, but they extend them while also implementing targeted test-taking strategies. For this reason, we view ISEE test preparation as an opportunity to bolster middle and high school readiness. My Learning Springboard also offers specialized instruction for students with learning disabilities and/or heightened anxiety. These students also benefit from more time to learn, apply, and integrate testing content and strategies.

Over time we have found that the approach to ISEE test preparation that works best for families and students is one that allows for incremental improvements over time. We always start with diagnostic testing so that our recommendations are individualized, and we recommend this planning begin in January, February or March prior to the upcoming admissions season. We need this runway to effectively plan and implement both grade level and above grade level instruction in all areas of the test, including Verbal Reasoning (vocabulary development), Reading Comprehension, Quantitative Reasoning, Math Achievement, and 5-paragraph essay writing. ISEE preparation provides ample opportunity for enhancing executive function skills, such as planning with the end in mind, managing time more effectively, initiating and completing tasks, and controlling impulses and emotions.

Cramming for the ISEE is not effective. Taking the long-view for test preparation–making it a marathon, not a sprint–allows each student to adjust their pace based on numerous factors, such as diagnostic results, learning style, previous experiences, family and school commitments, and time for practice, practice, practice. Taking a longer-term approach allows each student to internalize the grade level material covered in their classroom and during test preparation sessions and firmly establish the building blocks to move towards mastery of above grade level material. Many of our students have commented that due to ISEE test preparation with My Learning Springboard faculty they feel better prepared for their school work and more confident when new material is introduced, especially in mathematics. This extended time frame for test preparation allows for true content mastery and creates a much better long-term value for students and families engaged in the process.

By Brad Hoffman, Board Certified Educational Planner and Learning Specialist, and Laurie Gross, Educational Consultant and Reading Specialist. Your child has always done well in school, so you reasonably assume that they’ll do well on the Independent School Entrance Exam (ISEE) as you pursue a school transition. So you have your child sit for an ISEE diagnostic test. You fully expect that your child will knock it out of the ballpark, since, after all, they are already

Your child has always done well in school, so you reasonably assume that they’ll do well on the Independent School Entrance Exam (ISEE) as you pursue a school transition. So you have your child sit for an ISEE diagnostic test. You fully expect that your child will knock it out of the ballpark, since, after all, they are already  January is always an important check-in time for our families with

January is always an important check-in time for our families with  It’s the holiday season, you’ve worked as hard as possible to keep up with your schoolwork AND write the Common App AND fill out endless application forms, and the response from your Early Decision school is a blow to the gut: a deferral. You wander around in dismay, devastated, embarrassed, not sure what to do next or how to wrap your head around the possibility that your first choice school has not sent you a hearty welcome!

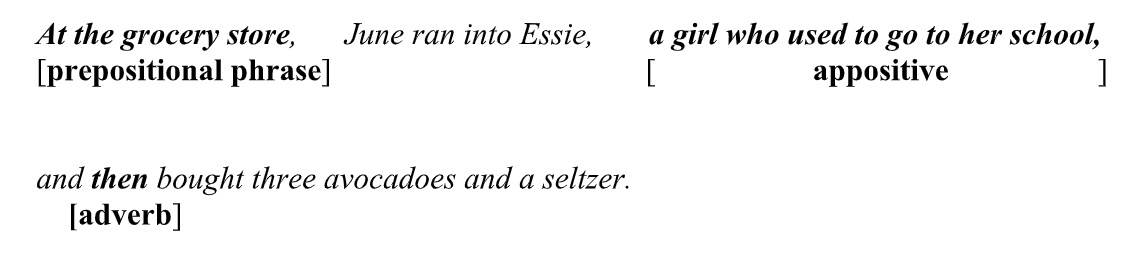

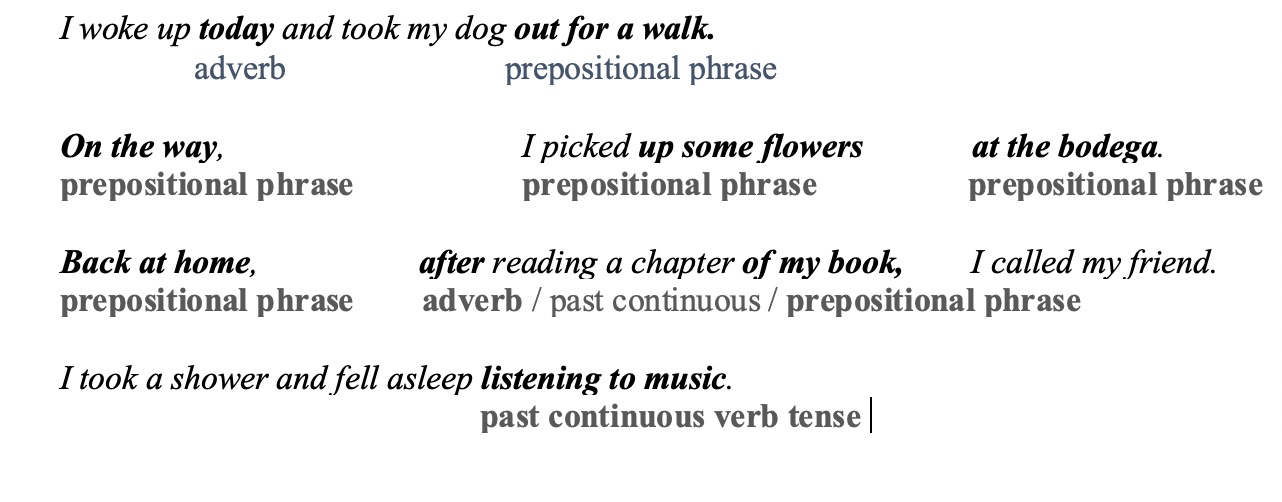

It’s the holiday season, you’ve worked as hard as possible to keep up with your schoolwork AND write the Common App AND fill out endless application forms, and the response from your Early Decision school is a blow to the gut: a deferral. You wander around in dismay, devastated, embarrassed, not sure what to do next or how to wrap your head around the possibility that your first choice school has not sent you a hearty welcome! In an age of auto-correct and casual texting, it’s common to think of grammar as a rigid set of rules that is unnecessary to study. Often, students have an intuitive grasp of language and what “sounds right” based on years of reading and writing. Educators face similar questions about studying grammar. In fact, debates over teaching grammar have been raging in the United States for the last fifty years. Those who advocate against teaching grammar argue that students will learn grammar in an organic way, through reading and writing. They state that grammar instruction is often prescriptive and focused on rules, thereby limiting student expression. Certainly, there are dreary and constricting ways of teaching and learning grammar, but can we ever separate our thoughts and ideas from the sentences we are using to express them?

In an age of auto-correct and casual texting, it’s common to think of grammar as a rigid set of rules that is unnecessary to study. Often, students have an intuitive grasp of language and what “sounds right” based on years of reading and writing. Educators face similar questions about studying grammar. In fact, debates over teaching grammar have been raging in the United States for the last fifty years. Those who advocate against teaching grammar argue that students will learn grammar in an organic way, through reading and writing. They state that grammar instruction is often prescriptive and focused on rules, thereby limiting student expression. Certainly, there are dreary and constricting ways of teaching and learning grammar, but can we ever separate our thoughts and ideas from the sentences we are using to express them?